How footwear, lifestyle and mindful movement shape your foundation for ageing well

When Balance Starts to Fade

Loss of balance is often described as a symptom of ageing, yet it is better understood as a loss of adaptation. The body’s ability to maintain stability depends on constant feedback between the feet, joints, eyes and inner ear. This conversation continues every second of every day. When one part of the system becomes less responsive, the others strain to keep the body upright.

For many older adults, this loss of stability leads to falls, which are one of the most common causes of injury and loss of independence in later life. Research shows that one in three people over the age of sixty-five experiences at least one fall each year, and even minor falls can reduce confidence and mobility for months afterwards (World Health Organization, 2021). The good news is that balance can be retrained at any age, and the earlier it is addressed, the lower the risk of both falls and fear of falling.

Ageing alone does not cause imbalance. The decline usually begins earlier through years of footwear that restricts movement, long periods of sitting, reduced outdoor activity and uneven muscle use. The small stabilisers in the feet and lower legs grow weaker, and the brain receives less information from the ground. This affects the way we stand, move and even how confident we feel in motion.

Restoring balance begins from the feet up by re-educating the body’s foundation to sense, respond and stabilise again.

How Modern Living Deconditions the Feet

The human foot evolved for varied terrain. Its arches act like springs, storing and releasing energy, while its sensory receptors provide detailed information about surface, load and pressure. Shoes have changed this natural function.

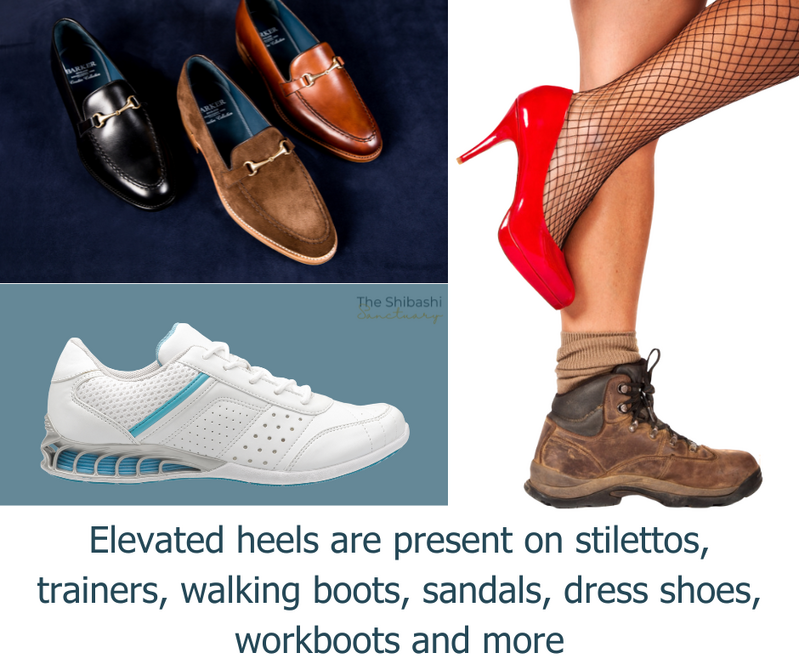

Supportive footwear reduces sensation, creating what researchers call sensorimotor amnesia, a loss of sensory input that leads to weaker reflexes and slower reactions (McKeon and Fourchet, 2015). High heels or rigid soles tilt the pelvis and spine, altering muscle tone throughout the kinetic chain. Even a small heel height increases compression in the lower back and restricts hip extension. Over years this pattern contributes to stiffness, fatigue and poor coordination.

Modern lifestyles compound the problem. Long periods of sitting switch off the gluteal muscles that should stabilise the hips and support balance during walking and standing. When the glutes are weak, the body relies on smaller muscles around the hips and lower back, which tire quickly and limit efficient movement. This adds to the strain created by footwear and poor posture, reducing both stability and power from the feet up.

This is why many people who describe themselves as clumsy or off balance are experiencing disconnection, not deterioration. The foundation is still there; it has simply been under-used.

The Body’s Balance System

Balance relies on an intricate sensory network known as the sensorimotor loop. Information travels from pressure receptors in the feet and joints to the spinal cord and brainstem, where it is integrated with input from the eyes and vestibular system. The brain then sends rapid corrective signals back to the muscles to maintain stability.

When the feet stop providing accurate feedback, the brain compensates by tightening larger muscles around the hips and spine. This increases rigidity rather than true stability. Studies show that older adults with weaker foot muscles display slower response times and greater sway when standing still (Menz et al., 2018). Strengthening the intrinsic foot muscles and improving ankle mobility reverses this pattern, improving both postural control and walking speed (Uritani et al., 2020).

The lesson is simple: strong, aware feet create faster communication with the brain, allowing balance reactions to happen before a fall occurs.

Foot Alignment: The First Step in Every Movement

Foot strength means little without alignment. How you place your feet shapes the way the rest of your body organises itself above. Turning the feet out or collapsing the arches rotates the legs inward, twists the knees and shifts load into the hips and lower back. Over time, this creates tension patterns that travel upward into the spine and shoulders.

Standing or walking with the feet straight forward allows the ankles, knees and hips to align in their natural position. It keeps the inner arches active, distributes weight evenly and encourages the toes to stabilise with each step. This alignment lets the forces of movement travel cleanly through the skeleton instead of being absorbed by overworked muscles.

I often describe it like the wheels of a car. When the wheels point straight ahead, the car moves smoothly in the direction it is meant to go. If they are even slightly turned out, wear begins to show on the tyres and undercarriage. The same is true for humans. When the feet turn out or roll in, every joint above compensates, and over time this creates unnecessary strain and gradual damage. Improved alignment reduces joint wear and tear by allowing forces to travel evenly through the body instead of being concentrated in one area.

I coach this position in every exercise because it changes everything. When someone stands with their feet parallel, the body begins to correct itself. The hips open, the spine lifts and breathing deepens naturally. Alignment is not cosmetic; it is functional. It gives the nervous system clear information about where the body is in space, allowing balance reflexes to do their job efficiently.

In Shibashi, this alignment also has energetic meaning. Straight, grounded feet align the Kidney meridians evenly, allowing qi to rise through both sides of the body without distortion. The result is steadier energy and greater balance, both physical and emotional.

The Nervous System’s Role

Stability is not just mechanical; it is neurological. The nervous system adjusts muscle tone based on perceived safety. When the brain senses instability, it increases background tension to protect the joints. Chronic tension then limits movement, reinforcing the very instability it tries to prevent.

This protective loop is influenced by stress. High cortisol levels reduce fine motor control and delay reflex timing (McEwen, 2016). Gentle rhythmic movement paired with slower breathing, as used in Shibashi, reduces this baseline tension through activation of the vagus nerve, shifting the body from fight or flight into rest and repair (Zaccaro et al., 2023). When the nervous system relaxes, movement becomes smoother and balance responses more accurate.

The Energetic View: Rooting the Body’s Qi

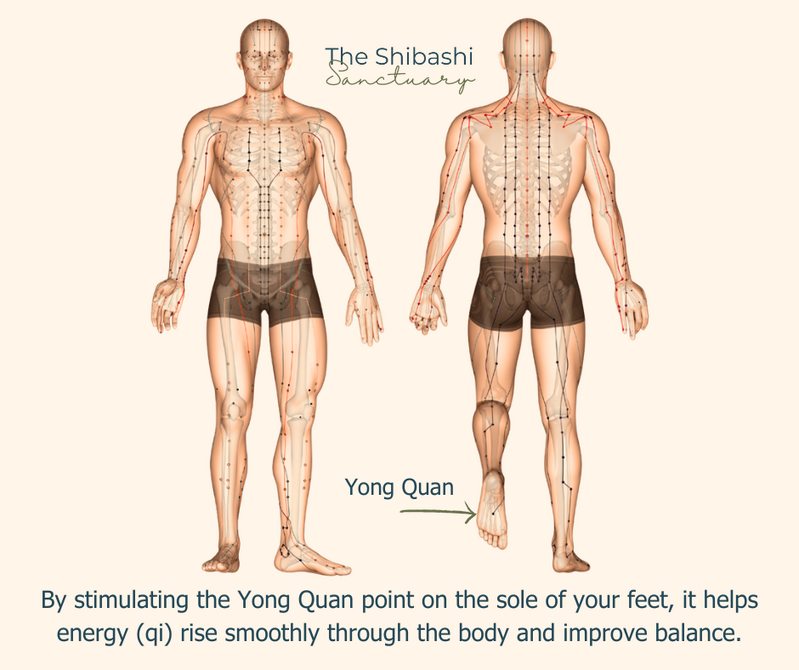

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the Kidney meridian begins at Yong Quan (Kidney 1) on the sole of the foot. It anchors qi, the body’s vital energy, and connects physical strength with emotional steadiness. When kidney energy is weak, people often describe feeling ungrounded or fearful. This emotional unease mirrors the physical experience of instability.

Shibashi strengthens this connection through movements that sink, root and flow upward from the soles. The downward focus gathers qi through the feet, while the upward expansion distributes it evenly through the body. In modern terms, this coordination of muscular activation and diaphragmatic breathing enhances postural integration and interoceptive awareness, the sense of internal balance that links body and mind.

Where Western physiology describes proprioception, TCM speaks of qi flow. Both point to the same reality: stability depends on clear communication between the body’s foundation and its centre.

How Shibashi Rebuilds the Foundation

Tai Chi Qigong Shibashi is structured around slow, circular patterns that engage multiple systems simultaneously. The practice strengthens the intrinsic muscles of the feet, trains joint alignment and restores rhythmic coordination between breath and movement.

When practised barefoot, sensory input from the soles reawakens the stabilising reflexes of the ankles and knees. The gentle shifting of weight stimulates the vestibular system, which fine-tunes balance and spatial orientation. Repetition creates neuroplastic change as the brain rewires its movement patterns through consistent, low-intensity feedback.

Physiologically, each breath-led motion helps regulate heart rate variability, an indicator of adaptability in the autonomic nervous system (Lehrer and Gevirtz, 2014). Energetically, the steady rhythm encourages the flow of qi through the Kidney and Liver meridians, supporting both grounding and flexibility. The result is not just stronger muscles, but a nervous system trained to stay calm and responsive.

Retraining Balance: A Guided Practice

Begin barefoot so the feet can feel and respond to the floor.

Stand on a firm, hard surface to start. Carpet or mats add instability and can be used later as a progression once balance improves.

Place your feet hip-width apart, directly underneath your hip joints and facing straight forward.

Check your alignment by drawing an imaginary line from the second toe through the centre of the knee and up the thigh. The femur should also face forward, stacking the joints straight up.

Balance your body weight evenly through both feet.

Soften your knees slightly, relax your shoulders and lengthen your neck through the crown of your head.

Take a few slow breaths through your nose and allow your body to settle.

Now, keeping your weight even, lift the heel of one foot slowly off the floor, feeling how the standing leg adjusts beneath you. Lower it gently back down. Repeat on the other side.

Once this feels steady, lift the heel again and continue until the whole foot floats just clear of the floor. Move with control.

Use a wall or the back of a sturdy chair for support if needed. Touch it only as much as gives you confidence. The aim is not to rely on it but to feel secure enough to explore your balance safely.

As you balance, notice how the ankle, foot and hip of the standing leg work together to keep you steady. Keep your gaze forward and your breath slow and even. Each repetition builds the connection between awareness, control and stability.

This exercise retrains the foot and ankle stabilisers, aligns the leg muscles and strengthens the reflexes that prevent falls. It also builds calm confidence, the essence of balance in both body and mind.

Ageing Well Means Adapting Well

The ability to balance is the ability to adapt. Ageing reduces recovery speed, not potential for improvement. The neuromuscular system remains plastic throughout life, meaning it can relearn efficiency through repetition and calm attention.

Practising Shibashi regularly retrains this adaptability. It restores strength from the feet up, steadies the breath and teaches the body to move as one integrated unit. The result is less strain, more confidence and a genuine reduction in fall risk.

From a TCM perspective, this daily regulation maintains the steady flow of qi that keeps the organs and emotions balanced. From a Western perspective, it keeps the sensory-motor systems tuned and the postural muscles active. Both describe the same truth: prevention is not about fighting decline, but maintaining connection.

Conclusion: Prevention from the Feet Up

Balance cannot be outsourced to footwear, technology or treatment; it must be practised. Strong, active feet keep the whole body and brain informed. A responsive nervous system keeps it coordinated. A calm mind keeps it adaptable. Alignment holds it all together.

Falls in later life are not inevitable. Most begin as small losses of strength, awareness or confidence that can be rebuilt through mindful practice. Each time you move with attention, you are not only training your muscles but also teaching your brain and nervous system how to recover faster and stay steady under pressure. The earlier you begin, the greater your protection against injury and the loss of confidence that often follows a fall.

Shibashi brings all of this together. Every movement becomes a conversation between the feet and the brain, the breath and the nervous system, the physical and the energetic. Each time you practise, you strengthen that conversation. Stability returns not through force, but through awareness, one step, from the feet up.

References

Lehrer, P. M. and Gevirtz, R. (2014) ‘Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work?’, Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 756.

McEwen, B. S. (2016) ‘The effects of chronic stress on health: insights into the stress response’, Molecular Psychiatry, 21 (8), pp. 1058–1070.

McKeon, P. O. and Fourchet, F. (2015) ‘Freeing the foot: integrating the foot core system into rehabilitation for lower extremity injury’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49 (5), pp. 290–295.

Menz, H. B., et al. (2018) ‘Foot problems as a risk factor for falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66 (9), pp. 1839–1848.

Sun, Y., Liu, J., Kong, J. and Yao, W. (2020) ‘Effective assessments of a short-duration poor posture and its impact on muscle fatigue’, Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 541974.

Uritani, D., et al. (2020) ‘Toe muscle strength and physical performance in older adults’, Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 20 (9), pp. 839–845.

Zaccaro, A., Palmieri, L., Piarulli, A. and Laurino, M. (2023) ‘Acute effects of breathing exercises on muscle tension and psychological stress’, Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1155134.

Zou, L., et al. (2019) ‘The effects of Tai Chi and Qigong on balance, fall risk and quality of life in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Frontiers in Medicine, 6, pp. 13–24.

Comments